TEMPUS Magazine redefines time, giving you a glimpse into all things sophisticated, compelling, vibrant, with its pages reflecting the style, luxury and beauty of the world in which we live. A quarterly publication for private aviation enthusiasts.

Issue link: http://tempus-magazine.epubxp.com/i/156069

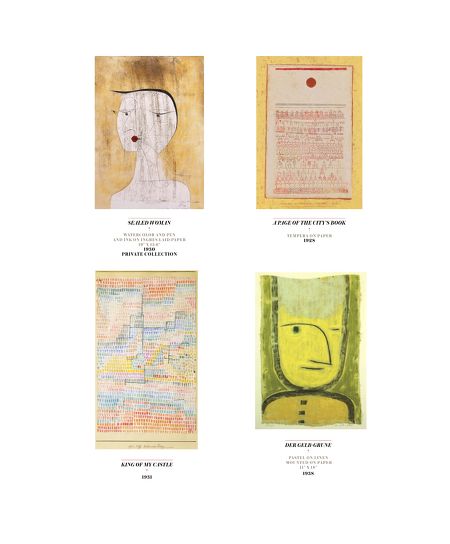

painting aircraft and working as a clerk. Nevertheless, the wholesale slaughter of men in the trenches deeply affected him and his artistic output. "The more horrifying this world becomes, the more art becomes abstract," he wrote, "while a world at peace produces realistic art." The war's carnage was too gruesome to re-create. Abstraction was the only possibility. Ironically, Klee's art career fourished in the war years. As the New York Times critic Roberta Smith has noted, "Maturity strikes around 1918; line and color come together…" Critics wrote about him widely while war raged, and sales were strong to capitalists, who had plenty of money to invest. Berlin's Sturm gallery even sold a postcard printed with a photo of Klee. In 1920, Klee received a telegram from the Bauhaus, the high temple of modernism, asking him to join the school as a master. The architect Walter Gropius had founded the Bauhaus in Weimar, Germany, the previous year. A pioneer of pareddown, geometrical design, Gropius preached melding form and function and abhorred decoration. Though its existence would be short-lived, the Bauhaus would exert tremendous infuence over the direction of architecture in the coming century. Gropius, who would later fee the Nazis and bring his brand of modernism stateside to Harvard University, wanted big names on the Bauhaus's faculty, and Klee wanted to teach. Gropius's concept was to mix artistry with artisanship, and the frst course Klee taught was bookbinding. He later tried his hand as a master in metalworking, glass painting, weaving, and drawing and also taught a popular course on the creative process, analyzing his students' as well as his own. Among the con- stantly squabbling faculty, Klee emerged as a calm, respected arbiter. Teaching had a direct impact on his art-making. The topics he discussed with his students were often still dancing in his head when he returned to his private studio. Hence, as art historian Boris Friedewald writes in his book Paul Klee: Life and Work, after lecturing about balance, Klee made a whimsical picture of a tightrope walker. The Bauhaus period was wonderfully creative for Klee, as he executed hundreds of works each year and never stopped inventing, whether cutting up and reassembling works, spray painting over cut-out shapes to create negative space, or pursuing "Square Paintings," off-kilter grids of seemingly random colors. Klee's star was rising—not only in Europe, but also in the United States. He had his frst solo show in the United States in 1924, at Société Anonyme, founded by the artists Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Katherine S. Dreier. A German-born artist and curator named Galka Scheyer began promoting him, along with Kandinsky, Feininger, and Alexei Jawlensky, as the Blue Four. The Viennese-born Hollywood flm director Josef von Sternberg cosponsored a Blue Four show in Los Angeles. Prominent collectors, such as Duncan Phillips, founder of the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., acquired numerous Klees, as did the Mexican artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, and the playwright Clifford Odets, who reportedly owned sixty. Alfred H. Barr, Jr., the infuential founding director of the Museum of Modern Art, soon caught on. In 1930, he made Klee the subject of a solo show, the frst at MoMA devoted to a living European In 1930, Barr made Klee the subject of a solo show, the frst at MoMA devoted to a living European painter. Fall 2013 . Tempus-Magazine.com 63 PAUL KLEE