TEMPUS Magazine redefines time, giving you a glimpse into all things sophisticated, compelling, vibrant, with its pages reflecting the style, luxury and beauty of the world in which we live. A quarterly publication for private aviation enthusiasts.

Issue link: http://tempus-magazine.epubxp.com/i/156069

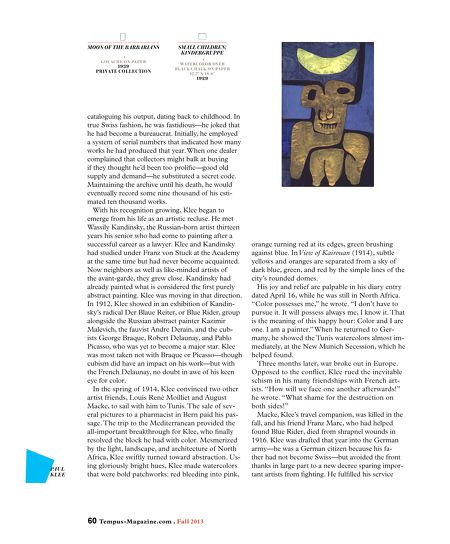

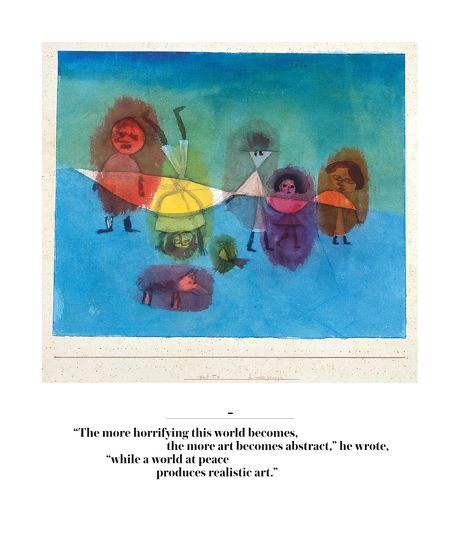

MOON OF THE BARBARIANS G OUAC H E O N PA P E R 1939 PRIVATE COLLECTION SMALL CHILDREN; KINDERGRUPPE WATE RC O LO R OV E R B L AC K C H A L K O N PA P E R 1 7. 7 " X 1 8.8" 1929 PAUL KLEE cataloguing his output, dating back to childhood. In true Swiss fashion, he was fastidious—he joked that he had become a bureaucrat. Initially, he employed a system of serial numbers that indicated how many works he had produced that year. When one dealer complained that collectors might balk at buying if they thought he'd been too prolifc—good old supply and demand—he substituted a secret code. Maintaining the archive until his death, he would eventually record some nine thousand of his estimated ten thousand works. With his recognition growing, Klee began to emerge from his life as an artistic recluse. He met Wassily Kandinsky, the Russian-born artist thirteen years his senior who had come to painting after a successful career as a lawyer. Klee and Kandinsky had studied under Franz von Stuck at the Academy at the same time but had never become acquainted. Now neighbors as well as like-minded artists of the avant-garde, they grew close. Kandinsky had already painted what is considered the frst purely abstract painting. Klee was moving in that direction. In 1912, Klee showed in an exhibition of Kandinsky's radical Der Blaue Reiter, or Blue Rider, group alongside the Russian abstract painter Kazimir Malevich, the fauvist Andre Derain, and the cubists George Braque, Robert Delaunay, and Pablo Picasso, who was yet to become a major star. Klee was most taken not with Braque or Picasso—though cubism did have an impact on his work—but with the French Delaunay, no doubt in awe of his keen eye for color. In the spring of 1914, Klee convinced two other artist friends, Louis René Moilliet and August Macke, to sail with him to Tunis. The sale of several pictures to a pharmacist in Bern paid his passage. The trip to the Mediterranean provided the all-important breakthrough for Klee, who fnally resolved the block he had with color. Mesmerized by the light, landscape, and architecture of North Africa, Klee swiftly turned toward abstraction. Using gloriously bright hues, Klee made watercolors that were bold patchworks: red bleeding into pink, 60 Tempus-Magazine.com . Fall 2013 orange turning red at its edges, green brushing against blue. In View of Kairouan (1914), subtle yellows and oranges are separated from a sky of dark blue, green, and red by the simple lines of the city's rounded domes. His joy and relief are palpable in his diary entry dated April 16, while he was still in North Africa. "Color possesses me," he wrote. "I don't have to pursue it. It will possess always me, I know it. That is the meaning of this happy hour: Color and I are one. I am a painter." When he returned to Germany, he showed the Tunis watercolors almost immediately, at the New Munich Secession, which he helped found. Three months later, war broke out in Europe. Opposed to the confict, Klee rued the inevitable schism in his many friendships with French artists. "How will we face one another afterwards!" he wrote. "What shame for the destruction on both sides!" Macke, Klee's travel companion, was killed in the fall, and his friend Franz Marc, who had helped found Blue Rider, died from shrapnel wounds in 1916. Klee was drafted that year into the German army—he was a German citizen because his father had not become Swiss—but avoided the front thanks in large part to a new decree sparing important artists from fghting. He fulflled his service